LewTheShoe

Seeking Skill-based Meritocracy... More HP Less DF

- Joined

- Apr 21, 2016

- Messages

- 4,739

- Points

- 593

A few months ago, in the context of a political discussion downstairs in the Podium, I wrote about my Aunt Zhanna, who as a young girl in 1941 escaped from a Nazi death march, and survived the Holocaust by literally "hiding in the spotlight." After the war, she was aided by an army captain (yes, my father) who broke all the rules to arrange her immigration to the United States. A forum member sent a kind message of appreciation, and suggested that I post the story here because a lot of us don't visit the Podium. So that's what I'm doing, and hope y'all don't mind. It's mildly edited from my original post.

Photo: Book cover of "Hiding In The Spotlight," written by my cousin Greg about his mother (my aunt). Published 2009. The title of this thread and some of the photos come from the book, but I wrote the rest of it myself.

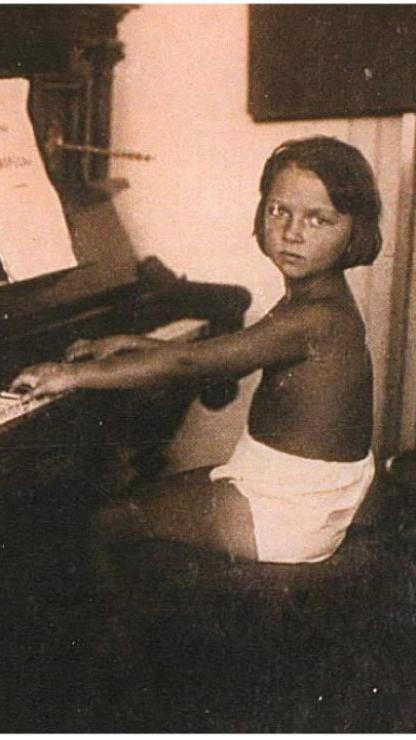

Growing up in Kharkov, the second largest city in Ukraine, Zhanna Arshanskaya was a child prodigy of piano. Her father owned a small candy shop. His most prized possession was a decent quality German-made upright piano. In the tiny apartment, his two young daughters would practice at home, and also go to the home of a neighborhood lady for lessons. (Photo: Zhanna at age 5 or 6.)

Both Zhanna and her younger sister Frina were talented, but Zhanna was exceptional. By the age of six, she had performed on live radio. By ten, she was enrolled to study at Kharkov's finest music conservatory, full scholarship. Surely, the grand concert halls of St. Petersburg and Moscow were in her future.

Then came Hitler.

In June 1941, three million German soldiers and more than 3,000 tanks crossed the Soviet border. Extermination of Soviet Jews followed soon after. In December 1941, Nazis rounded up the 16,000 Jews in Kharkov; marched them 12 miles out of the city center to Drobitsky Yar; slaughtered them with machine guns; and piled their bodies in the deep ravines. To save bullets, some of the small children were thrown in alive to freeze to death among their dead or dying parents.

Zhanna and her family were Jewish. They were a family of six... Zhanna was 14 and her sister Frina was 12; also there was their father, mother, and paternal grandparents. The massacre was carefully documented in meticulous German official records... names, addresses, dates, everything. History says no one escaped the death march to Drobitsky Yar. Indeed, the memorial there lists Zhanna and Frina among the perished, their names carved in the stone like all the others. But history made at least one faulty assumption, missed at least one crucial fact.

A few miles before reaching Drobitsky Yar, Zhanna's father approached a young soldier guarding the march. This guard was likely a Ukraine POW who had no particular axe to grind. Perhaps he helped the Nazis because it meant a chance to survive, while his mates back in the POW camp were starving to death. Zhanna's father spoke urgently to the guard, pleading mistaken identity, claiming the family were not Jews. He told the guard that two young girls were going to run into the woods, and offered a bribe of his gold pocket watch for the guard to look away. He said to Zhanna, "I don't care what you have to do. Just live!"

Somehow, it worked. The sisters hid in the forest, then crept back to town under cover of darkness. They found a friend of a friend... gentiles who hid the girls in their home for two weeks, and helped them concoct non-Jewish identities... fake names, fake stories about why they had no parents. The girls hoped to wait out the war in an orphanage. They were in constant fear that their non-Jewish cover stories would get blown.

The orphanage had a creaky old piano. Zhanna's sublime playing upon this ancient relic was heard by a piano tuner who was a Nazi sympathizer, and he knew the owner of a theater/night club frequented by German soldiers. Zhanna and Frina (fake names Anna and Marina Morozova) were pressured to perform at this theater. They were deathly afraid to appear... what if someone in the audience recognized them? What if someone shouted out, "She's a Jew?" But they were even more terrified to refuse to appear. What if someone asked questions about the talented sisters who refused to play for the German officers and troops?

They played. And the Germans took notice. “Anna” and “Marina” spent the rest of the war as captive entertainers for the unsuspecting Nazis, performing in large concert halls for soldiers, in private dining quarters for officers and black-booted SS... fearful every moment of being discovered or betrayed as Jews... literally hiding in the spotlight!

A few years ago, I asked Zhanna what it was like to walk onto the stage and look out at an audience of that same German army that had massacred her family. I said, "It must have been cruel to have to summon up a musical performance for the pleasure of those Nazi monsters?"

"Yes" she said, "it was cruel and I was so scared. I was scared to do it, and scared not to do it. At times I felt the weight of it all upon me." And then she looked me straight in the eye, and her stare was pure steel. "But I never cried. I had no more tears left. I just would remember what my father told me... 'I don't care what you have to do. Just live!' That's what he told me and that's what I did."

When the war ended the sisters were sent to a displaced persons camp near Munich. Once again, an old, out-of-tune piano shaped their fate. My father was commander of that camp. It was his job to assist civilian war victims to return to their homelands or to other settlements. Many were eager to go home, but some were terrified at the prospect. Some feared persecution by former friends and neighbors. Many had nothing to return to... and that included Zhanna and Frina on both counts.

I've heard stories from that camp. People telling my father... "If you have to send me back there, just kill me now, please dear God just kill me now." (For the record, Dad didn't kill any of them! He did discover his true calling in life. He spent the rest of his career (another 35 years) working to assist war refugees around the world as a career employee of the Department of State.)

Dad was a lover of classical music. He saw Zhanna and Frina playing that old piano in the social hall, and he knew that he was witnessing spectacular talent. After months of struggling over their situation, he hatched a plan to slip the two girls onto a ship of Holocaust survivors bound for New York. A lot of rules got broken to make it happen, but I'm sure the statute of limitations has expired by now.

I don't know if the refugees on that ship entered the United States via Ellis Island, but it certainly would be fitting if they did... under the welcoming gaze of the Statue of Liberty. No money, no English language... what could go wrong?

Zhanna and Frina had step-by-step instructions from my father, written in English and Russian. 1) Bookstore for a Russian - English dictionary. 2) Grand Central Station. 3) Southbound train to Charlottesville, Virginia. 4) Taxi to a tiny rented farmhouse in Crozet, Virginia complete with a hand-drawn map of driving instructions. But it was late at night, it was raining, and the map was confusing. The taxi driver got hopelessly lost. Finally he found the house where the army captain's wife - my mother - waited. The driver refused to accept payment for the fare, his gesture to welcome the two Russian girls to America.

Part B of my father's plan commenced the following year when he returned home from Germany. He wrote letters to a range of music conservatories seeking auditions. Lots of phone calls. Pulled a lot of strings. Scored an audition at the highly-regarded Peabody Conservatory in Baltimore. Both girls nailed their auditions. They had genuine musical talent, and they had a compelling backstory of perseverance and survival. Both bagged scholarship offers! They were ecstatic, bubbling with joy.

Dad cut the celebration short. "OK," he said, "now we go to New York." To my father, the Peabody was an excellent backup plan, but the holy grail was the Juilliard School in New York. His baby brother, my Uncle David, had studied viola there. Dad knew it was the best music school in America. At the Juilliard, the sisters auditioned before a three-member panel, and again, both were offered full-boat scholarships.

Dad's plan had worked. He went home. There was nothing more he could do for these young ladies. It was now up to them.

Epilogue: At some later point, a summer internship brought Zhanna to the same place my Uncle David was playing in a string quartet. This was where they met, and later they married. As near as I can tell, there never was any raised eyebrow or negative comment about a Jewish woman entering into our many-generations Virginian and Christian family.

Both David and Zhanna had long, distinguished careers on the faculty of the prestigious Indiana University School of Music, and also played numerous concerts, some prominent and others obscure. Uncle David died in 1975 while in his late fifties. Zhanna is now 93, and lives in Atlanta.

Zhanna in 1961, age 34 years...

Zhanna in 2012, age 85 years...

In 2006, my cousin Greg travelled to Ukraine to research his book, "Hiding In The Spotlight." At the Drobitsky Yar memorial, he was surprised to find his mother's name listed (erroneously) as a victim who perished in the Nazi massacre. There was no error about the names of her father, mother, and grandparents, who did actually perish before the Nazi machine guns...

Photo: Book cover of "Hiding In The Spotlight," written by my cousin Greg about his mother (my aunt). Published 2009. The title of this thread and some of the photos come from the book, but I wrote the rest of it myself.

**************************************

Growing up in Kharkov, the second largest city in Ukraine, Zhanna Arshanskaya was a child prodigy of piano. Her father owned a small candy shop. His most prized possession was a decent quality German-made upright piano. In the tiny apartment, his two young daughters would practice at home, and also go to the home of a neighborhood lady for lessons. (Photo: Zhanna at age 5 or 6.)

Both Zhanna and her younger sister Frina were talented, but Zhanna was exceptional. By the age of six, she had performed on live radio. By ten, she was enrolled to study at Kharkov's finest music conservatory, full scholarship. Surely, the grand concert halls of St. Petersburg and Moscow were in her future.

Then came Hitler.

In June 1941, three million German soldiers and more than 3,000 tanks crossed the Soviet border. Extermination of Soviet Jews followed soon after. In December 1941, Nazis rounded up the 16,000 Jews in Kharkov; marched them 12 miles out of the city center to Drobitsky Yar; slaughtered them with machine guns; and piled their bodies in the deep ravines. To save bullets, some of the small children were thrown in alive to freeze to death among their dead or dying parents.

Zhanna and her family were Jewish. They were a family of six... Zhanna was 14 and her sister Frina was 12; also there was their father, mother, and paternal grandparents. The massacre was carefully documented in meticulous German official records... names, addresses, dates, everything. History says no one escaped the death march to Drobitsky Yar. Indeed, the memorial there lists Zhanna and Frina among the perished, their names carved in the stone like all the others. But history made at least one faulty assumption, missed at least one crucial fact.

A few miles before reaching Drobitsky Yar, Zhanna's father approached a young soldier guarding the march. This guard was likely a Ukraine POW who had no particular axe to grind. Perhaps he helped the Nazis because it meant a chance to survive, while his mates back in the POW camp were starving to death. Zhanna's father spoke urgently to the guard, pleading mistaken identity, claiming the family were not Jews. He told the guard that two young girls were going to run into the woods, and offered a bribe of his gold pocket watch for the guard to look away. He said to Zhanna, "I don't care what you have to do. Just live!"

Somehow, it worked. The sisters hid in the forest, then crept back to town under cover of darkness. They found a friend of a friend... gentiles who hid the girls in their home for two weeks, and helped them concoct non-Jewish identities... fake names, fake stories about why they had no parents. The girls hoped to wait out the war in an orphanage. They were in constant fear that their non-Jewish cover stories would get blown.

The orphanage had a creaky old piano. Zhanna's sublime playing upon this ancient relic was heard by a piano tuner who was a Nazi sympathizer, and he knew the owner of a theater/night club frequented by German soldiers. Zhanna and Frina (fake names Anna and Marina Morozova) were pressured to perform at this theater. They were deathly afraid to appear... what if someone in the audience recognized them? What if someone shouted out, "She's a Jew?" But they were even more terrified to refuse to appear. What if someone asked questions about the talented sisters who refused to play for the German officers and troops?

They played. And the Germans took notice. “Anna” and “Marina” spent the rest of the war as captive entertainers for the unsuspecting Nazis, performing in large concert halls for soldiers, in private dining quarters for officers and black-booted SS... fearful every moment of being discovered or betrayed as Jews... literally hiding in the spotlight!

A few years ago, I asked Zhanna what it was like to walk onto the stage and look out at an audience of that same German army that had massacred her family. I said, "It must have been cruel to have to summon up a musical performance for the pleasure of those Nazi monsters?"

"Yes" she said, "it was cruel and I was so scared. I was scared to do it, and scared not to do it. At times I felt the weight of it all upon me." And then she looked me straight in the eye, and her stare was pure steel. "But I never cried. I had no more tears left. I just would remember what my father told me... 'I don't care what you have to do. Just live!' That's what he told me and that's what I did."

**************************************

When the war ended the sisters were sent to a displaced persons camp near Munich. Once again, an old, out-of-tune piano shaped their fate. My father was commander of that camp. It was his job to assist civilian war victims to return to their homelands or to other settlements. Many were eager to go home, but some were terrified at the prospect. Some feared persecution by former friends and neighbors. Many had nothing to return to... and that included Zhanna and Frina on both counts.

I've heard stories from that camp. People telling my father... "If you have to send me back there, just kill me now, please dear God just kill me now." (For the record, Dad didn't kill any of them! He did discover his true calling in life. He spent the rest of his career (another 35 years) working to assist war refugees around the world as a career employee of the Department of State.)

Dad was a lover of classical music. He saw Zhanna and Frina playing that old piano in the social hall, and he knew that he was witnessing spectacular talent. After months of struggling over their situation, he hatched a plan to slip the two girls onto a ship of Holocaust survivors bound for New York. A lot of rules got broken to make it happen, but I'm sure the statute of limitations has expired by now.

I don't know if the refugees on that ship entered the United States via Ellis Island, but it certainly would be fitting if they did... under the welcoming gaze of the Statue of Liberty. No money, no English language... what could go wrong?

Zhanna and Frina had step-by-step instructions from my father, written in English and Russian. 1) Bookstore for a Russian - English dictionary. 2) Grand Central Station. 3) Southbound train to Charlottesville, Virginia. 4) Taxi to a tiny rented farmhouse in Crozet, Virginia complete with a hand-drawn map of driving instructions. But it was late at night, it was raining, and the map was confusing. The taxi driver got hopelessly lost. Finally he found the house where the army captain's wife - my mother - waited. The driver refused to accept payment for the fare, his gesture to welcome the two Russian girls to America.

Part B of my father's plan commenced the following year when he returned home from Germany. He wrote letters to a range of music conservatories seeking auditions. Lots of phone calls. Pulled a lot of strings. Scored an audition at the highly-regarded Peabody Conservatory in Baltimore. Both girls nailed their auditions. They had genuine musical talent, and they had a compelling backstory of perseverance and survival. Both bagged scholarship offers! They were ecstatic, bubbling with joy.

Dad cut the celebration short. "OK," he said, "now we go to New York." To my father, the Peabody was an excellent backup plan, but the holy grail was the Juilliard School in New York. His baby brother, my Uncle David, had studied viola there. Dad knew it was the best music school in America. At the Juilliard, the sisters auditioned before a three-member panel, and again, both were offered full-boat scholarships.

Dad's plan had worked. He went home. There was nothing more he could do for these young ladies. It was now up to them.

**************************************

Epilogue: At some later point, a summer internship brought Zhanna to the same place my Uncle David was playing in a string quartet. This was where they met, and later they married. As near as I can tell, there never was any raised eyebrow or negative comment about a Jewish woman entering into our many-generations Virginian and Christian family.

Both David and Zhanna had long, distinguished careers on the faculty of the prestigious Indiana University School of Music, and also played numerous concerts, some prominent and others obscure. Uncle David died in 1975 while in his late fifties. Zhanna is now 93, and lives in Atlanta.

Zhanna in 1961, age 34 years...

Zhanna in 2012, age 85 years...

In 2006, my cousin Greg travelled to Ukraine to research his book, "Hiding In The Spotlight." At the Drobitsky Yar memorial, he was surprised to find his mother's name listed (erroneously) as a victim who perished in the Nazi massacre. There was no error about the names of her father, mother, and grandparents, who did actually perish before the Nazi machine guns...